The Romantic Era

The turn of the 18th century found the old continent in a state generalised crisis. The rapid pace of urbanisation and industrialisation of European countries, after its disintegration feudal society, resulted in a series of rapid developments economically, socially and culturally.

The intense financial reclassifications led to a significant drop to the standards of living of a large part of the population. This fact had as a result the explosion and spread of various revolutionary movements with social demands, culminating in the French Revolution of 1789, when people were asking for freedom and equality.

Schubert represented a turning point in musical history. Classical forms of his predecessors, but while his own musical style was essentially Classical, his inspiration looked forward to the age of Romanticism. One of the key features of Romantic music is its strong association with other art-forms, particularly literature or painting. Schubert responded instinctively to the poetry and drama of the great literary figures of his time: Goethe, Friedrich Schiller, Friedrich Ruckert, Friedrich Klopstock, and Ludwig Holty. Their writings, even when dealing with historical figures or events, expressed ordinary human emotions, love, happiness, sorrow and the beauty of the natural world.

The other great Romantic theme was a response to nature, especially in its wilder aspects. Earlier generations had sought to tame and cultivate the landscape; but in the late 18th century artists and writers – spurred on by Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-78) and his rejection of rationalism – reacted against the artificial moral code of Classical writers and philosophers, who believed in a neatly ordered world.

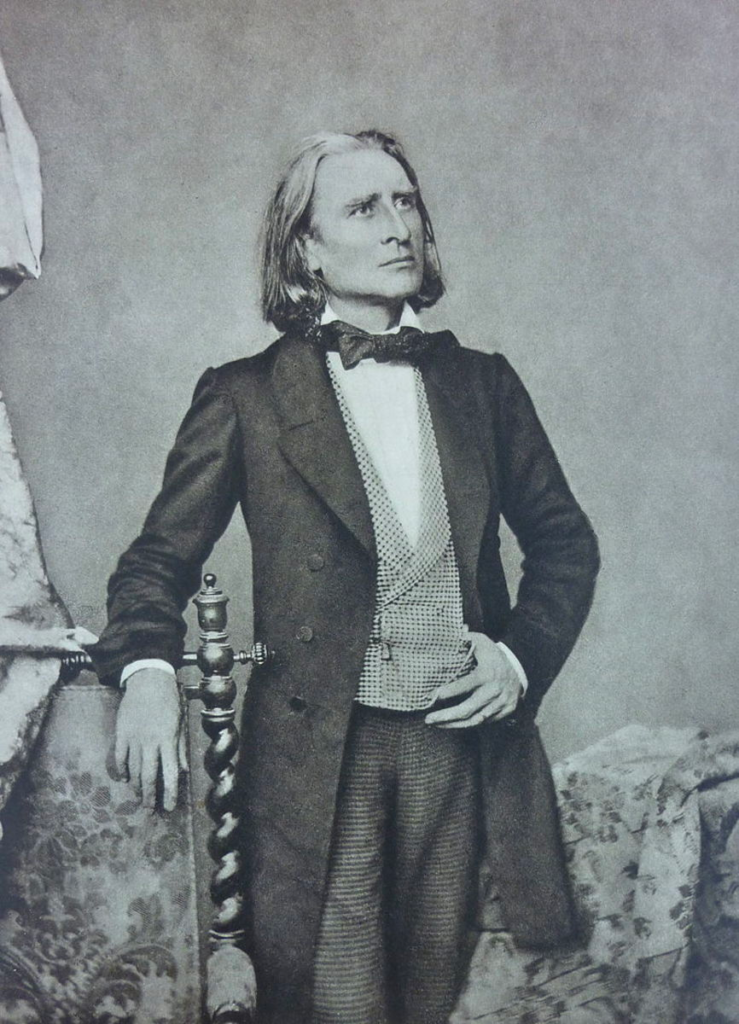

The other hallmark of musical Romanticism was its emphasis on the individual – either the composer, fighting a lonely battle against incomprehension and intolerance, or the performer. The 19th century saw the rise of the star performer and with it a division between creator and executant which became progressively more marked in the 20th century. Many 19th-century composers (Chopin, Liszt, Brahms, Paganini) carried on the tradition followed by Mozart and Beethoven in writing music for themselves to perform, but they also began to write for other virtuoso executants, such as the pianists Clara Schumann, Eugen d’ Albert and his wife Teresa Carreno; the violinists Joseph Joachim, dedicatee of concertos by Brahms and Bruch, Ferdinand David, for whom Mendelssohn wrote his concerto and Pablo de Sarasate for whom Lalo, Bruch and Saint-Saens wrote concertos; and the clarinettist Richard Muhlfeld for whom Brahms wrote his great chamber works for that instrument.